Child Sexual Exploitation

This guidance outlines the roles and responsibilities of relevant agencies and the procedures practitioners should follow to ensure the safety and well-being of children and young people who are at risk of/experiencing CSE.

This procedural guidance summarises the responsibility of professionals and volunteers to intervene effectively to prevent the sexual exploitation of children. For many, this will mean being alert to the ways in which young people can become vulnerable to CSE, the indicators that they are being drawn into exploitative situations and knowing how to report these concerns. For others, who have more specific safeguarding responsibilities, it will involve complex work to support victims and disrupt and prosecute perpetrators. For everyone, it will involve questioning attitudes and beliefs that may get in the way of recognising that children are being sexually exploited and providing the consistent, determined non-judgemental support they and their families need.

1. Introduction

1.1 Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a form of child sexual abuse. It is a complex form of abuse and can often be difficult for those working directly with children to identify and assess. The indicators for CSE can sometimes be mistaken for ‘normal adolescent behaviours’. Children from any background or community can be the victim of exploitation, therefore all practitioners should be open to the possibility that the children they work with might be affected.

2. What is CSE?

2.1 ‘Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity

(a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or

(b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator.

The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.’ (DfE, 2017)

2.2 Like all forms of child sexual abuse, child sexual exploitation can:

- affect any child or young person (male or female) under the age of 18 years, including 16 and 17 year olds who can legally consent to have sex;

- still be abuse even if the sexual activity appears consensual;

- include both contact (penetrative and non-penetrative acts) and non-contact sexual activity;

- take place in person or via technology, or a combination of both;

- involve force and/or enticement-based methods of compliance and may, or may not, be accompanied by violence or threats of violence;

- occur without the child or young person's immediate knowledge (through others copying videos or images they have created and posting on social media).

- be perpetrated by individuals or groups, males or females, and children or adults.

- be a one-off occurrence or a series of incidents over time, and range from opportunistic to complex organised abuse; and

- Is typified by some form of power imbalance in favour of those perpetrating the abuse. Whilst age may be the most obvious, this power imbalance can also be due to a range of other factors including gender, sexual identity, cognitive ability, physical strength, status, and access to economic or other resources.

2.3 Young people can often be groomed into trusting their abuser and may not understand that they're being abused; believing they're in a loving, consensual relationship.

3. Grooming

3.1 Sexual exploitation is commonly characterised by the grooming of young people. This process is carried out by perpetrators to gain their trust. Perpetrators often target children who are already vulnerable – who may have troubled family histories and/or be bullied outside of the home and socially isolated. Once the young people are thought to be sufficiently emotionally involved, violence and intimidation is often used to ensure compliance. In addition, perpetrators may give drugs and alcohol to victims and encourage addiction in order to ensure they become dependent on them for the supply of these substances.

3.2 Grooming methods are used to gain the trust of a child and their parents. This often means that the victim does not recognise that they have been exploited or forced and believe that they have chosen or consented. However, children are not considered able to give 'informed consent' to their own exploitation.

4. Indicators of Risk / Vulnerability

4.1 Sexually exploited children come from a range of backgrounds and may have no additional risk factors or vulnerabilities, therefore, professionals should always keep an open mind to the possibility that a child may be at risk of exploitation. However, children can be at increased risk of sexual exploitation if they have any additional vulnerabilities, as perpetrators may target them and try to exploit these vulnerabilities.

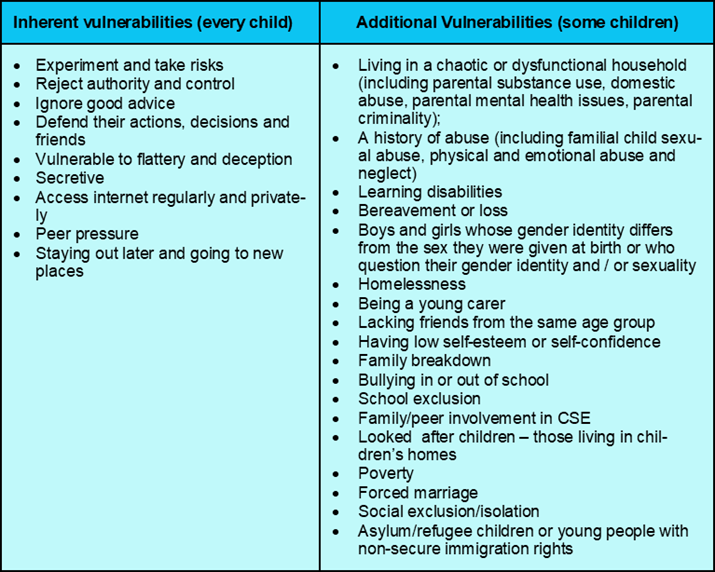

4.2 There are inherent factors that make any child vulnerable to CSE. Some children display additional vulnerabilities. The table below lists some of the vulnerabilities that can increase the likelihood of a child becoming a victim of CSE.

Table 1 List of Vulnerabilities

(NB: This is not an exhaustive list)

5. Recognising child sexual exploitation

5.1 CSE is often a hidden harm, and explicit evidence of exploitation may not be evident. Children and young people may not disclose their experiences. This can be out of fear of recriminations, feelings of shame and guilt or because they do not recognise their own exploitation or they fear they will not be believed. Child sexual exploitation (CSE) can be very difficult to identify. Warning signs can easily be mistaken for 'normal' teenage behaviour.

5.2 Children and young people who are being sexually exploited may display certain behaviours:

- displaying inappropriate sexualised behaviour for their age

- being fearful of certain people and/or situations

- displaying significant changes in emotional wellbeing

- being isolated from peers/usual social networks

- being increasingly secretive

- having money or new things (such as clothes or a mobile phone) that they can't explain

- spending time with older individuals or groups

- being involved with gangs and/or gang fights

- having older boyfriends or girlfriends

- missing school and/or falling behind with schoolwork

- persistently returning home late

- returning home under the influence of drugs/alcohol

- going missing from home or care

- being involved in petty crime such as shoplifting

- spending a lot of time at hotels or places of concern

- recruiting others into exploitative situations

- evidence of sexual bullying and/or vulnerability through the internet and/or social networking sites

- involvement in offending

- receipt of gifts and money from unknown sources

- unexplained physical injuries and other signs of physical abuse

- changed physical appearance - for example, weight loss

- self-harm / thoughts of or attempts at suicide

- sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy and / or terminations

6. Professional Response

6.1 Referral

6.1.1 A referral must be made as soon as possible when any concern of Significant Harm as a consequence of child sexual exploitation becomes known. Any agency or practitioner who has concerns that a child may be at risk of harm should contact the relevant MACH or CHub. If there is concern about a child’s immediate safety, the Police should be contacted on 999.

6.1.2 When considering making a referral, you will also need to balance the need for confidentiality with your responsibility to share information to protect the child. Where possible, you should always ascertain the views of the child, and keep them, and their parents/carers informed about your actions.

6.1.3 An Early Help Assessment may be crucial in the early identification of children and young people who need additional support due to being vulnerable to child sexual exploitation.

6.1.4 Support and interventions should be proportionate and based on the child's needs identified during the assessment.

6.1.5 If a case is open and allocated then the referrer must contact the allocated Social Worker, manager or Service Manager either in writing, or by telephone followed by confirmation in writing within 2 days. If the case is closed, then a new referral will need to be made.

Making & Response to a Referral

Local Authority Contacts (please click on the relevant logo on the linked page)

6.2 Assessment

6.2.1 Once the MACH / CHUB or the child’s lead professional confirms the identified risk(s), a Child & Family Assessment may be triggered.

6.2.2 A Teeswide Child Exploitation Screening Tool can be completed either at the point of referral by the referring professional or as part of the assessment. The screening tool is considered at the VEMT Practitioners Group.

6.3 VEMT Practitioner Group Meetings

6.3.1 Multi-agency VEMT Practitioner Group (VPG) Meetings take place weekly in each of the Children’s Social Care areas. Chaired by Children’s Services, the VPG provide a multi-agency forum with responsibility for assessing and reducing the risk of exploitation for children. These meetings will also include representatives from Cleveland Police, Education and Health and any other agencies appropriate to the children being discussed.

6.3.2 Each week, the VPG will consider new referrals / open cases with a view to ensuring clear and regular communication and effective co-ordination of activities between all multi-agency partners across Teesside. The VPG will review and assess the effectiveness of, and adapt, interventions in accordance with changing risk/circumstances.

7. Useful Practice Tools (on this website)

8. Useful Links and Resources (on this website)

- Partnership Information Sharing Form - Cleveland Police

- Tees Missing from Home / Care Protocol

- Wrong Hands Toolkit:

9. Further information