Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is recognised internationally as a grave violation of the human rights of girls and women. It is illegal in England and Wales under the FGM Act (2003). It comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

1. Introduction and overview

1.1 Even though FGM is a child protection issue which has a major impact on the health and wellbeing of the child – it can take place within otherwise loving and caring families, who genuinely believe they are acting in the best interest of the child. FGM must always be regarded as causing significant harm.

1.2 It should also be remembered that FGM can be the “norm” with specific communities and may play a part of acceptance and fulfilling the role of a female within the community expectations. Where that community is a minority within a wider society there may be immense psychological impact of a person who has been/will be subject to FGM, as they are caught between the specific expectations of their community and the wider cultural expectations of the wider society.

1.3 Parents and others who have subjected daughters or plan to subject daughters to FGM do not intend it as an act of abuse; they believe it is in the girl's best interest to conform to their prevailing custom. Agencies should work together to promote a better understanding of the damaging consequences to physical and psychological health of FGM. Local policy (especially in areas where there are communities within FGM which is prevalent) should contain a prevention strategy based on education and partnership. Wherever possible the aim must be to work in partnership with parents, families and communities to protect children through parent’s awareness of the harm caused to the child.

2. Legal Position

2.1 FGM is a criminal offence under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003. The act also makes if offence for UK nationals or permanent residents to carry out, or aid, abet, counsel or procure the carrying out of FGM abroad – including for countries in which the practice is legal.

3. Mandatory reporting

3.1 Section 5B of the 2003 Act introduces a mandatory reporting duty which requires regulated health and social care professionals and teachers in England and Wales to report ‘known’ cases of FGM in under 18s which they identify in the course of their professional work to the police. The duty applies from 31 October 2015 onwards.

3.2 ‘Known’ cases are those where either a girl informs the person that an act of FGM – however described – has been carried out on her, or where the person observes physical signs on a girl appearing to show that an act of FGM has been carried out and the person has no reason to believe that the act was, or was part of, a surgical operation within section 1(2)(a) or (b) of the FGM Act 2003.

3.3 The duty is a personal duty which requires the individual professional who becomes aware of the case to make a report; the responsibility cannot be transferred. The only exception to this is if you know that another individual from your profession has already made a report; there is no requirement to make a second. Reports should be made by telephone or writing to the police.

3.4 It is recommended that you make a report orally by calling 101, the single non-emergency number. When you call 101, the system will determine your location and connect you to the police force covering that area. You will hear a recorded message announcing the police force you are being connected to. You will then be given a choice of which force to be connected to – if you are calling with a report relating to an area outside the force area which you are calling from, you can ask to be directed to that force.

3.5 Reports under the duty should be made as soon as possible after a case is discovered, and best practice is for reports to be made by the close of the next working day. You should act with at least the same urgency as is required by your local safeguarding processes. In order to allow for exceptional cases, a maximum timeframe of one month from when the discovery is made applies for making reports. However, the expectation is that reports will be made much sooner than this.

3.6 Further guidance is available from this link: Mandatory Reporting of Female Genital Mutilation – procedural information

4. Prevalence of FGM

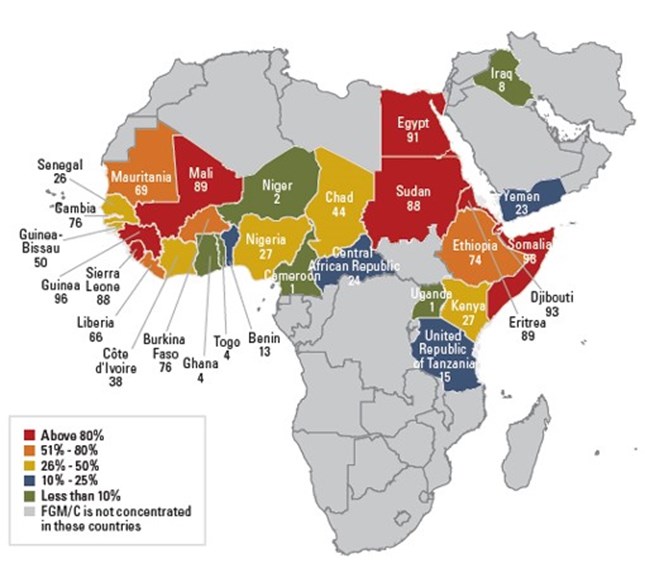

4.1 It is estimated that more than 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone female genital mutilation in the countries where the practice is concentrated. Furthermore, there are an estimated 3 million girls at risk of undergoing female genital mutilation every year. The majority of girls are cut before they turn 15 years old.

4.2 Female genital mutilation has been documented in 30 countries, mainly in Africa, as well as in the Middle East and Asia. Some forms of female genital mutilation have also been reported in other countries, including among certain ethnic groups in South America. Moreover, growing migration has increased the number of girls and women living outside their country of origin who have undergone female genital mutilation or who may be at risk of being subjected to the practice in Europe (WHO, 2013).

Source : UNICEF, 2013

5. Impact on children

5.1 FGM is carried out on children who cannot understand the full implications or exercise informed choice. The practice is painful and can have serious health implications (including death in some circumstances through blood loss or infection) both at the time of procedure and in later life. FGM can cause the following:

- Severe pain: cutting the nerve ends and sensitive genital tissue causes extreme pain. Proper anaesthesia is rarely used and, when used, is not always effective. The healing period is also painful and can be prolonged.

- Excessive bleeding: (haemorrhage)

- Shock: can be caused by pain, infection and/or haemorrhage.

- Genital tissue swelling: due to inflammatory response or local infection.

- Infections: may spread after the use of contaminated instruments (e.g. use of same instruments in multiple genital mutilation operations), and during the healing period.

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV): the direct association between FGM and HIV remains unconfirmed, although the cutting of genital tissues with the same surgical instrument without sterilization could increase the risk for transmission of HIV between girls who undergo female genital mutilation together.

- Urination problems: these may include urinary retention and pain passing urine.

- Impaired wound healing: can lead to pain, infections and abnormal scarring

- Death: can be caused by infections, including tetanus and haemorrhage that can lead to shock.

- Psychological consequences: the pain, shock and the use of physical force by those performing the procedure are mentioned as reasons why many women describe FGM as a traumatic event.

Long-term health risks (occurring at any time during life)

- Pain: due to tissue damage and scarring that may result in trapped or unprotected nerve endings.

- Infections:

- Chronic genital infections: with consequent chronic pain. Urinary tract infections: If not treated, such infections can ascend to the kidneys, potentially resulting in renal failure, septicaemia and death.

- Menstrual problems: result from the obstruction of the vaginal opening.

- Female sexual health: removal of, or damage to highly sensitive genital tissue, especially the clitoris, may affect sexual sensitivity and lead to sexual problems, such as decreased sexual desire and pleasure, pain during sex, difficulty during penetration, decreased lubrication during intercourse, reduced frequency or absence of orgasm (anorgasmia). Scar formation, pain and traumatic memories associated with the procedure can also lead to such problems.

- Obstetric complications: FGM is associated with an increased risk of Caesarean section, post-partum haemorrhage, recourse to episiotomy, difficult labour, obstetric tears/lacerations, instrumental delivery, prolonged labour, and extended maternal hospital stay. The risks increase with the severity of FGM.

- Psychological consequences: some studies have shown an increased likelihood of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders and depression. The cultural significance of FGM might not protect against psychological complications.

5.2 A child may be considered to be at risk if it is known that older girls in the family have been subject to the procedure. Pre-pubescent girls of 7 to 10 are the main subjects, though the practice has been reported amongst babies.

6. Potential indicators that FGM may have/could occur

- Planned holidays/absence from school

- Changes in behaviour or avoiding certain activities e.g. school PE following the procedure

- Child referring to a “special procedure”

- Health experts become aware that FGM has taken place on another family member e.g. from examination of a mother during pregnancy

- Mother has recently come to this country so the culture of her country of origin is likely to have great influence, for example - 89% of females in Eritrea have FGM (UNICEF, 2013)

- A female UBB/child has an older sibling or cousin who has undergone FGM

- The family indicate that there are strong levels of influence held by elders and/or elders are involved in bringing up female children

- The woman/family believe FGM is integral to cultural or religious identity

- The family has a limited level of integration within UK community

- Parents have limited access to information about FGM and do not know about the harmful effects of FGM or UK law

7. Action to be taken

7.1 Where a professional or agency believes a child is likely to suffer of has suffered FGM a child protection referral must be made.

7.2 In planning any intervention it is important to consider the significance of cultural factors. Any intervention is more likely to be successful if it involves workers from, or who have detailed knowledge of the community concerned. FGM is a one-off event of physical abuse (albeit one that may have grave permanent sexual, physical and emotional consequences), not an act of repeated abuse and organisational responses need to recognise this.

7.3 If the child has already suffered FGM the meeting (the type of meeting would depend on the level of concern which you would discuss in conjunction with your manager) will need to consider carefully whether to continue enquiries or whether to assess the need for support services. The meeting should consider any other children in the family or household who may be at risk of FGM in the future.

7.4 A girl who has already been genitally mutilated should not normally be subject to a Child Protection Conference unless additional protection concerns exist. She should be offered counselling and medical help. Consideration must be given to any other female siblings at risk. She should be offered a referral to the Paediatric Forensic Network, Children and Young People’s Clinic, The Great North Children’s Hospital, Newcastle for a holistic assessment. This referral should be made by social worker on behalf of the multiagency team.

7.5 A girl believed to be in danger of genital mutilation may be made subject to a Child Protection Plan with the primary category of physical abuse and an application for a FGM Prevention order should be considered. The Child Protection Plan should reflect an approach of awareness raising, education, support and persuasion.

8. Helpline

8.1 The Female Genital Mutilation Helpline is a UK-wide service. It operates 24/7 and is staffed by specially trained child protection helpline counsellors who can offer advice, information, and assistance to members of the public and to professionals. Counsellors are also to make referrals, as appropriate, to statutory agencies and other services.

The helpline can be contacted on: 0800 028 3550 and emails sent to fgmhelp@nspcc.org.uk

8.2 The aim of this specialist helpline is to improve the safeguarding of children in the UK by increasing the detection and protection of children at risk or who have become victims of female genital mutilation. It will also facilitate, as necessary, the sharing of information with police and relevant agencies so that intelligence can be gathered and appropriate action taken against those who facilitate female genital mutilation against children. It will work in the same way as the main NSPCC helpline.

9. Relevant links

- HALO Project - The Halo Project Charity based in Middlesbrough supports victims of Honour Based Violence, FGM and Forced Marriages by providing appropriate advice and support to victims. Working with key partners it will also provide the required interventions and advice necessary for the protection and safety of victims.

- FGM Awareness (Gov.UK)

- FGM Guidance for Health Professionals

- FGM Information and Guidance (NSPCC)

- FGM Mandatory Reporting in Healthcare

- FGM Mandatory Reporting Flowchart (NHS England)

- FGM Multiagency Guidance (NE FGM Partnership Board)

- FGM Multiagency Guidance (Gov.UK)

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office advice

- How to Record Disclosure of FGM – Guidance for Health Staff in the Tees area

- Mandatory Reporting of Female Genital Mutilation – procedural information (Gov.UK)